In May 2014, I reported on my efforts to learn what the feds know about me whenever I enter and exit the country. In particular, I wanted my Passenger Name Records (PNR), data created by airlines, hotels, and cruise ships whenever travel is booked.

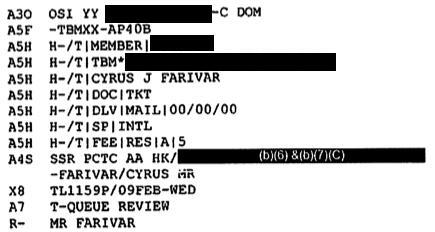

But instead of providing what I had requested, the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) turned over only basic information about my travel going back to 1994. So I appealed—and without explanation, the government recently turned over the actual PNRs I had requested the first time.The 76 new pages of data, covering 2005 through 2013, show that CBP retains massive amounts of data on us when we travel internationally. My own PNRs include not just every mailing address, e-mail, and phone number I've ever used; some of them also contain:

- The IP address that I used to buy the ticket

- My credit card number (in full)

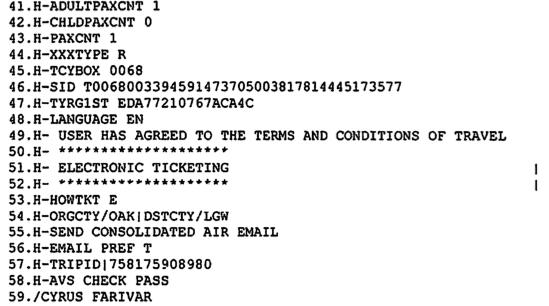

- The language I used

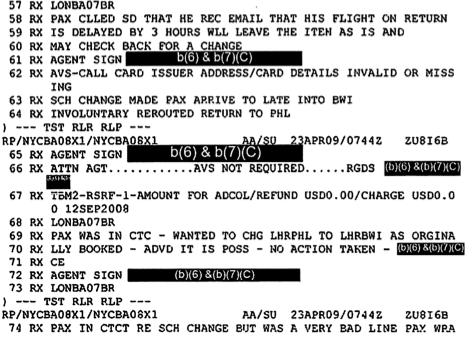

- Notes on my phone calls to airlines, even for something as minor as a seat change

The breadth of long-term data retention illustrates yet another way that the federal government enforces its post-September 11 "collect it all" mentality.

Parsing PNRs

Parts of my PNRs, such as travel itineraries, were easy to understand. Others were nearly impossible to parse, so I enlisted the help of Edward Hasbrouck, a travel writer who has extensively researched (and even filed lawsuits over) PNRs. He told me that PNRs like mine are created for domestic flights, too, but that it's only for international travel that data is routinely given to CBP.

I was most surprised to see my credit card details—full card number and expiration date—published unredacted and in the clear. Fortunately, that credit card number has long expired, but I was nonetheless appalled to see it out there. American Airlines, which had created that particular PNR in 2005, did not immediately respond to my request for comment on how or why such detailed personal information would show up here. (In other instances, the majority of the number was X’d out.)

As I looked through the logs, I also saw notes, presumably made by call center staff, recording each time I had tried to make a change by phone. Hasbrouck said that this is typical and that it's one of the downsides of global outsourcing—the people I’m talking to probably have no idea that everything they write down will be kept in American government records for years.

“There’s no sense on the airline call center staff that they may or may not be aware that anything they put in may be in your permanent file with the Department of Homeland Security,” Hasbrouck said. “There’s no training in data minimization. They are empowered to put things in people’s files with the government. I think that’s pretty disturbing.”

Travel sites (such as Travelocity) and airlines (such as American) all recorded the basic information one might expect, like payment and contact details, but only some of them kept detailed records of calls. It turns out that whatever the site chooses to put into its PNR will almost certainly be handed over to CBP and will remain in your file for years.

PNRs can also include personal information about someone's travel, such as whether they request special meals (possibly revealing religion) or if they need special accommodations (possibly revealing a health condition). The fact that PNRs can be so revealing is part of the longstanding hangups between such data sharing between the United States and the European Union.

Just metadata?

Travel sites like Travelocity also pass information to the federal government. In July 2007, I booked a flight on Travelocity on American Airlines from Oakland to Dallas Fort Worth to London Gatwick and back. The site recorded a huge amount of information on me: name, address, phone, e-mail address, credit card number (again, in the clear), what seats I asked for, the language I used on the site, whether I was traveling with anyone else (I wasn’t), whether any traveling companions were adults or children, and whether I preferred to be contacted by e-mail.

Hasbrouck pointed out that the more information the airlines choose to retain, the more of an opportunity the government has to build a profile on me. “They have seat assignments [and] could probably search who is seated next to you for social network analysis,” he said. “You have no way of knowing when you’re using this website which information they are storing.”

“This is not to catch people under suspicion; this is for the purpose of finding new suspects,” Hasbrouck added.

I asked Travelocity about its practices and received a statement from Keith Nowak, a company spokesman.

"As the ticketing agents to the airlines, travel agencies like Travelocity routinely provide ticketing and other relevant passenger data to the airlines to help facilitate passenger flight requests," he said, declining to answer further specific questions. "Once this data has been transferred, the airlines use the data for appropriate operational purposes, and the airlines determine how and when the data may be shared with other parties. As a partner in this process, Travelocity consistently complies with all relevant data privacy and data security requirements."He declined to respond to how or why my credit card number was transmitted in the clear.

Fred Cate, a law professor at Indiana University, said that my story raises a lot of questions about what the government is doing.

“Why isn’t the government complying with even the most basic cybersecurity standards?” Cate said. “Storing and transmitting credit card numbers without encryption has been found by the Federal Trade Commission to be so obviously dangerous as to be ‘unfair’ to the public. Why do transportation security officials not comply with even these most basic standards?”

The goal of PNR collection, according to CBP, is "to enable CBP to make accurate, comprehensive decisions about which passengers require additional inspection at the port of entry based on law enforcement and other information."

This information is retained for quite some time in government databases. CBP publicly states that PNR data is typically kept for five years before being moved to “dormant, non-operational status.” But in my case, my earliest PNR goes back to March 2005. A CBP spokesperson was unable to explain this discrepancy.

“No wonder the government can’t find needles in the haystack—it keeps storing irrelevant hay," Cate told me. "Even if the data were fresh and properly secured, how is collecting all of this aiding in the fight against terrorism? This is a really important issue because it exposes a basic and common fallacy in the government’s thinking: that more data equates with better security. But that wasn’t true on 9/11, and it still isn’t true today. This suggests that US transportation security officials are inefficient, incompetent, on using the data for other, undisclosed purposes. None of those are very encouraging options."

"No wonder they didn’t want you to know what they had about you,” he added.

Giving up

What does this all mean in terms of how I book international travel? Frankly, not much, since I have no real choices. Like everyone else, I'm at the mercy of the websites that I entrust with my data.

Sure, I could (and do) routinely obscure my IP address with a VPN, but that doesn't do a whole lot when authorities already have more personal information about me. My VPN may help thwart an IP logging and searching algorithm—but Hasbrouck wondered if it might actually make me stand out more.

I could also employ a Julian Assange-like tactic, only buying last-minute tickets at an airport and in person. But that’s a lot harder when traveling with others, and it's almost always significantly more expensive. Traveling is difficult enough already without adding more stress to the equation.Seeing these travel records captured and stored for years on end reminded me of the other all-encompassing, blanket surveillance tools that I’ve been reporting on over the last few years, including license plate readers, fake cell towers (stingrays), and telecom metadata.

We now live in a world where it’s increasingly difficult to prevent the authorities from capturing information on one’s movements or communications. Is it "just metadata"? Yes, much of the time. But despite what the government wants you to believe, metadata can be exceptionally revealing.

reader comments

183